In May and June I made three trips on the Long Island Rail Road via trains departing from and returning to Pennsylvania Station. Of course I've been to Long Island many other times before that, usually by rental car or catching a ride with friends. But on one of my recent trips I noticed a stone marker above a southern stairway entrance to Penn Station's LIRR waiting room that tells the reader, "You Are Here." Above the words is an architectural blueprint-like rendering of what the old station used to look like when viewed from the south. Despite the marker's lack of context or explanation, it ignited my curiosity about the old days.

Truth be told, I've long known the basic history of the station, namely that the above-ground portion of it was torn down in the 1960s to make way for the current Madison Square Garden. I knew that its loss caused a community uproar that eventually lead to the formation of

the

NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. But it was the nuts and bolts of the old station that I wanted to get to know–its "footprint," if you will. And so for the past few weeks I've been trying to track down a book of photographs that I remember seeing last year, titled

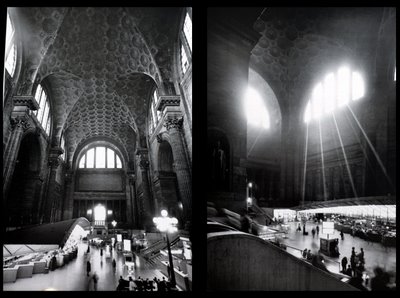

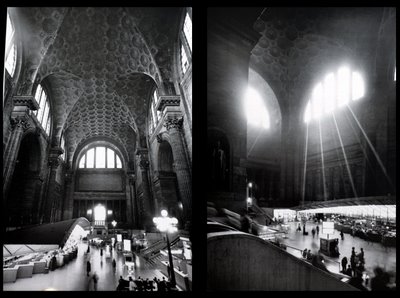

"The Destruction of Penn Station." The other day, after checking every bookstore I could think of, I finally found a copy, appropriately, at the Borders bookstore at One Penn Plaza. As the book's title suggests, it's rather heavy with pictures showing the station's dismantling from late 1963 until the middle of 1966. The photographer, Peter Moore, lived near Penn Station and so it was very easy for him to make regular trips to document the process. In all, he made about thirty trips throughout the two and a half years of the station's deconstruction. In the few pictures at the beginning of the book, Moore does a nice job of capturing the dignity of the station in its last months (Concourse at left and Main Waiting Room below). In fact, those were the pictures that I found myself looking at the most. I found a lot of other pictures elsewhere, online mostly, including this

collection, that show the station in its heyday, from completion in 1910 up until the early 1960s.

In the book there are some nice essays as well, one of which quotes Thomas Wolfe from his book "You Can't Go Home Again," when the main character, George Webber, walks into Penn Station's Main Waiting Room:

"The station, as he entered it, was murmurous with the immense and distant sound of time. Great, slant beams of moted light fell ponderously athwart the station's floor, and the calm voice of time hovered along the walls and ceiling of that mighty room, distilled out of the voices and movements of the people who swarmed beneath. It had the murmur of a distant sea, the langorous lapse and flow of waters on a beach. It was elemental, detached, indifferent to the lives of men...Few buildings are vast enough to hold the sound of time, and...there was a superb fitness in the fact that one which held it better than all others should be a railroad station."Known primarily for his photographs of avant-garde performances, Moore (1932-1993) worked briefly at Life Magazine's darkrooms. In the 1950s he was an assistant to the photographer O. Winston Link. He hung out with David Heath and Garry Winogrand and he even participated in a workshop hosted by W. Eugene Smith. He eventually became Senior Technical Editor of Modern Photography Magazine until 1989. "The Destruction of Penn Station" was edited by his wife, Barbara, and published in 2000. The book is wonderful and I'm totally grateful for Moore's "humble, evidentiary work" (a phrase borrowed from Joel Meyerowitz) that documents the station's dismantling.

The architecture critic Vincent Scully famously wrote that with the old station, "One entered the city like a god." With its replacement, "One scuttles in now like a rat." It's hard not to agree, especially considering how low the ceilings are in some areas of the subway connections/entrances. Taking a few laps in and around Penn Station, a few words come to mind: crowded, maze, tunnel, cramped, underground, artificial light. For reference, here are some random shots of the Penn Station of 2008:

And below are a few overall pictures I've taken inside Madison Square Garden (Republican National Convention in 2004, a boxing match also in 2004, and the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show in 2005).

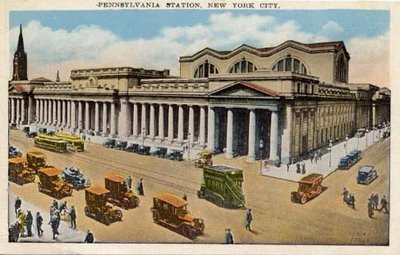

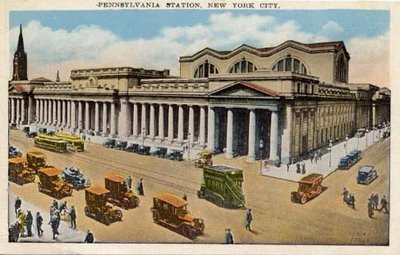

The original Penn Station station was built by the architects

McKim, Mead and White. It was based, in part, on the Roman baths of Caracalla. The Beaux-Arts style building was widely considered to be a masterpiece of architectural classicism, and it was the biggest indoor space in New York City at the time. I think it's important to realize that the original station was built when the automobile was in its infancy and that it connected New York City with the continental United States for the first time. By the 1960s, however, maintaining the aging station had become too costly. And the Pennsylvania Rail Road had been struggling to bring revenue into the station. Taking it down and replacing it with something more commercial must've seemed like the easiest route. I'm not going to get into the politics of why it was torn down, or even

current plans to resurrect the station in the Farley Post Office Building across the street. But looking back, one can easily see the forces of capitalism at play.

I think it would have been cool to take pictures inside the old station. I suspect that the

available light in its western-most concourse area was much-loved by photographers for decades. My favorite picture by Louis Faurer is a picture from Penn Station (right). When I first began studying Peter Moore's photographs, I had a hard time figuring out which direction was which. But eventually it came to me (much like the time I figured out where that famous

Grand Central Station image was taken from) that if you start with the Main Waiting Room and orient yourself accordingly to the incoming sunlight, it's very easy to tell which way is east and which way is west. On the exterior it was a little more difficult to tell which Avenue was which (7th or 8th), unless of course the Empire State Building was in the background of the photograph.

I've been writing this post for weeks, in fits and starts. It has occupied a large part of my thinking about NYC history lately. But how can somebody who's never set foot in the old station even begin write about it with authority? I guess anybody who knows me knows I have a pretty strong sense of nostalgia, photographic in particular. In the end, thankfully, we have the photos. The saddest thing to deal with is the fact that the documenting of the destruction of Penn Station was likely much more unmonitored and, therefore, considered much less suspicious than, the documenting of the reconstruction of the World Trade Center has been (Editor's Note: Peter Moore did seek, and receive, permission from the railroad's PR department and was granted access to otherwise restricted demolition areas, with no hard hat required). Forty-five years after the fact, it doesn't seem right that there aren't more photographic books dedicated to this topic (the destruction). No doubt forty-five years from now there'll be dozens of photography books detailing the rebuilding of the WTC.

The New York Times, in its "Farewell to Penn Station" editorial dated October 30, 1963, said it best: "Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tinhorn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed."

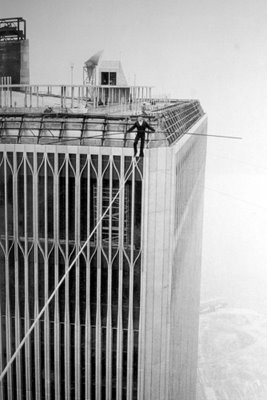

I'm a little slow in writing about a great movie that opened as I was out of town last week. It's called "Man On Wire" and I had been eagerly awaiting its opening. Watching it was the first thing I did when I got back into town this week. "Man On Wire" is a documentary (directed by James Marsh) about Philippe Petit, a French tightrope artist who rigged a wire between the twin towers of the World Trade Center and made eight crossings over the course of 45 minutes on the morning of August 7, 1974. The movie details the several years leading up to the walk and it features some great footage from two of his other famous tightrope performances: between the towers of the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris (1971) as well as between two towers at the entrance of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1973). I've been a huge fan of Petit's ever since I bought his book, "To Reach The Clouds" when it came out in 2002. The book gets very detailed about the logistics of how he and his cohorts achieved access to the towers, how they got the wire rigged, etc. It was published six months after 9/11 and so it ends on a more sombre, memorial tone than the movie. "Man On Wire" has a decidedly more triumphant feel, and 9/11 is never mentioned directly.

I'm a little slow in writing about a great movie that opened as I was out of town last week. It's called "Man On Wire" and I had been eagerly awaiting its opening. Watching it was the first thing I did when I got back into town this week. "Man On Wire" is a documentary (directed by James Marsh) about Philippe Petit, a French tightrope artist who rigged a wire between the twin towers of the World Trade Center and made eight crossings over the course of 45 minutes on the morning of August 7, 1974. The movie details the several years leading up to the walk and it features some great footage from two of his other famous tightrope performances: between the towers of the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris (1971) as well as between two towers at the entrance of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1973). I've been a huge fan of Petit's ever since I bought his book, "To Reach The Clouds" when it came out in 2002. The book gets very detailed about the logistics of how he and his cohorts achieved access to the towers, how they got the wire rigged, etc. It was published six months after 9/11 and so it ends on a more sombre, memorial tone than the movie. "Man On Wire" has a decidedly more triumphant feel, and 9/11 is never mentioned directly.